I was trying to register for my second year at UBC in 1965.

I had no family financial support. My personal persona was that of a long-haired hippy. I was $100 short of having enough money to register for the fall session, and despaired of finding a way to get it. As a last-ditch desperate gambit, I approached the Dean’s office in Buchanan Building to see if there was any scholarship or bursary that might be available to me.

Entering the office, I saw two ladies whose sole objective seemed to be to shield Dean Gage from riff-raff who would interrupt his work. I haltingly began to stutter out my need, but a few questions about my marks soon made it clear that I had no more hope than a snowball’s in a hot country of getting any money from any of the hundred or two bursaries out there, none of which specified their support of a second year student with poor grades, no sports ability, and no connection to any business or union that supported the young of its members.

Elapsed time, 40 seconds, and I was brusquely deflected back out the door, my last hope extinguished. As I began to pull the door open, I heard a loud magisterial voice emanating from the inner office, calling out to the lady who had begun to usher me out, “Let the Young Man Come IN!”. With a disapproving scowl and a shake of her head, the guardian directed me through a door which I now saw was half open, allowing the occupant to have overheard the office conversation. As I passed into the room, I saw a distinguished figure rise from behind his desk, walk toward me, put his hand on my shoulder, and direct me to sit down, while closing the door and directing his assistant to hold his calls.

With kind eyes and a caring voice, he soon extracted from me all the details about my family, my sisters, my ill mother, my financially straitened father, my poor marks, my hopes for the future—in fact, everything about me—perhaps even my blood type! I held nothing back, and felt myself on the verge of tears when I thought about how I was working 40 hours/ week while still trying to go to university.

After 15 minutes of close attention, Dean Gage told me in the kindliest manner possible, that although there was no bursary or scholarship available to me, there was another answer to my dilemma. Reaching into his own pocket, he pulled out a hundred dollar bill (the amount I was lacking to register) and told me to pay it back whenever I could. I could not help but cry at his kindness—as many others had. Leaving the office, I realized I had someone who cared about me at the university, and this affected my attitude to my classes in a very easily predictable manner.

I paid the loan back by Christmas. Nor did he forget me. Three years later, as I took my BA degree, he warmly greeted me on the stage as he handed me my scroll. A year later, after I had taken my MA and President Gage had retired, he saw me on the campus and greeted me with questions about my family that showed he remembered every detail of my life, and that he was proud of me.

Some years later, as I received my Ph.D., I was walking across campus with a friend and Walter Gage walked toward us. Seeing me, he immediately changed direction and walked, hand on my shoulder, with us for a good distance, again recalling every detail of my life and filling me with the warmth of human compassion and caring, an emotion which had been in short supply elsewhere in my life.

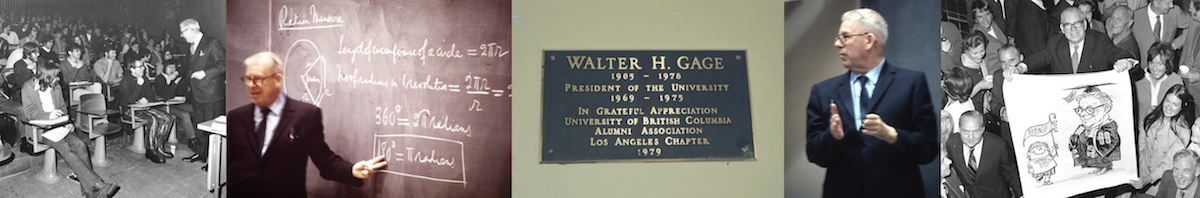

Walter Gage was a symbol of all a university president should be: caring, compassionate, and kindly. I have never met his equal in these qualities, and I was blessed to have his goodness shine on my life. He was a truly noble example of the best in humanity, and I still love to look at his signature on my diploma on the wall.

Let the Young Man Come In is a fitting epitaph for Walter Gage, and a wonderful mantra for the rest of us examples of true humanity.

Tom McKeown

BA, MA, PhD

Recent Comments